Coming to Terms with Constraint (Yù)

How many of you remember sitting in class dazed and bewildered by the introduction of yet another new term that may or may not have been similar to a term that had previously been drummed into your head?

In this article, we’re going to look at constraint (yù) which refers to something that’s pent-up or unable to move.

Constraint (Yù) and Constraint Disorders (Yù Zhèng)

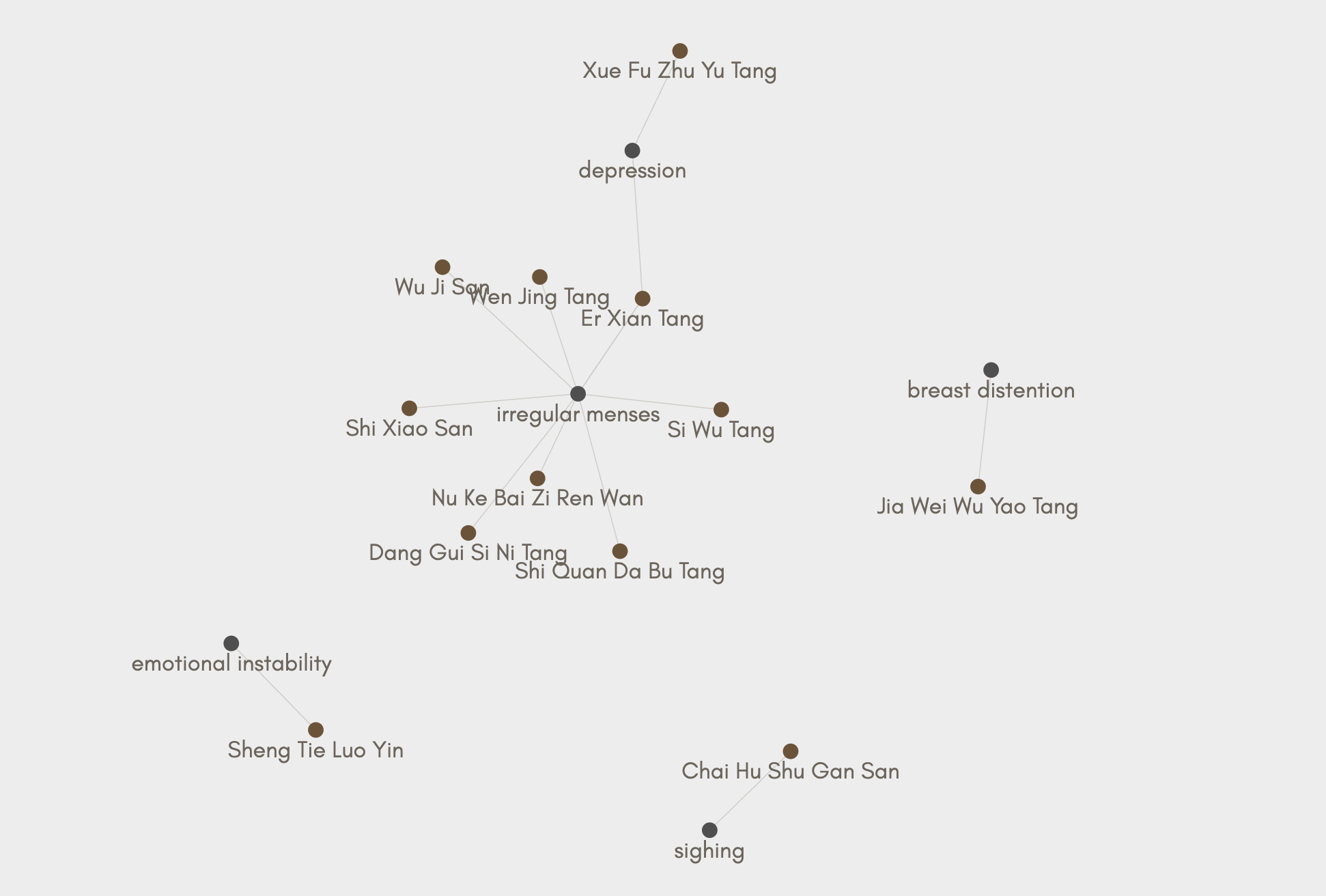

Review the following list of symptoms:

- Depression or emotional instability

- Chest oppression and pain

- Rib-side distention and pain

- Sighing

- Premenstrual breast distention

- Irregular menstruation

- Stringlike pulse

What pattern do you associate them with?

Depending on where you studied, who your teachers were, and what texts they used, your response will probably include one of the following:

- Binding depression of Liver qi (Deng)

- Depressed Liver qi (Wiseman & Feng)

- Liver qi stagnation (Maciocia)

- Liver constraint (Bensky et al.)

These are all associated with the terms gān yù, gān qì yù, or gān qì yù jíé.

Jason Blalack’s article, “Stagnation, Depression, Constraint, and Stasis: Terminological Clarification” states that “from an English point of view…Liver qi constraint, Liver qi depression & Liver qi stagnation are all the same!”

They’re all derived from the character for constraint, yù.

When you add the term “zhèng” at the end, you now have yù zhèng, commonly interpreted as constraint disorder. According to Jingyi & Xuemei, “this term is used to classify a group of disorders, such as anxiety and depression, which have been caused by emotional upset and qi stagnation.” They’re closely associated with the Liver.

Many texts simply equate yù zhèng with depression, in the Western sense of the term.

Sounds simple and clear, right? Constraint=depression=qi stagnation and, as a disorder, it relates to the Liver, emotional upset, and depression. Now we know we’re actually talking about the same thing with fellow practitioners. Case closed, let’s move on.

Not so fast.

There’s another word we have to come to terms with. History.

Historical Context

A good place to uncover the history of the term constraint (yù) is in Scheid et al.’s 2nd edition of Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies’ entry for Yuè Ju Wán. Escape Restraint Pill.

According to the authors, the term yù first appeared in early nonmedical texts referring to a tone that didn’t carry.

In the 3rd century BC, the idea of a hindered dynamic was applied to the body. Annals of Master Lu said if essence doesn’t flow, qi gets pent-up.

This concept was integrated into the five-phase doctrine of qi transformation in Chapter 71 of Basic Questions. Treatment strategies for each phase of constraint were recommended (e.g. thrust out wood constraint, discharge fire constraint).

Herbal medicine quickly integrated these strategies as a guiding principle for treating externally-contracted cold damage disorders. In the Shāng Hán Lùn, you find formulas treating yang qi constraint due to an external invasion of cold. Constraint was caused by external factors.

Things changed in the Song dynasty (960–1279), as physicians began to focus more on internal causes of disease. Chen Yan (1121-1190), a famous Song era physician, is credited as being the first to link constraint with emotional problems. But the idea didn’t take hold until much later.

The writer Wang Lü (1332 -1383) expanded the understanding of constraint beyond yang qi to the ascending and descending functions of the qi dynamic. Constraint became an important topic during the Jin-Yuan era as physicians came to regard the qi dynamic as playing the central role in all physiological and pathological processes.

In 1481, Essential Teachings of [Zhu] Dan-Xi stated that the majority of disorders of the human body arise from constraint. It could be due to irregular eating, excess cold or heat exposure, and excessive joy, anger, or anxiety. As explained by Zhu Dan-Xi’s disciple Dai Yuan-Li, qi constraint reflected stagnation of gathering qi, which is governed by the Lungs.

Did you catch that? The Lungs. Not the Liver.

Sometime during the Ming dynasty, physicians adopted Chen Yan’s earlier linking of constraint with the emotions. They began to define constraint “as a condition where a person was unable to express his feelings, leading to stagnation and the manifestation of physical symptoms.”

In modern times constraint is typically interpreted as qi stagnation due to an emotional cause. Since the Liver is intimately connected with both qi and the emotions, it has become the organ most closely associated with constraint, although any organ can be constrained.

Implications

As you can see, the understanding of the term yù, or constraint, has evolved over the centuries. This is important given Chinese Medicine is inclusive in nature.

For example, in herbal medicine, if we apply our modern understanding of constraint-as-depression to older formulas, we might choose one that’s less effective or inappropriate.

Or conversely, we might overlook a formula that could be exactly what our patient needs.

~ Dr. Susan D. West, DACM

Resources

Bensky, D., Clavey, S., & Stoger, E. (2004). Chinese herbal medicine: Materia medica (3rd edition). Eastland Press, Inc.

Blalack, J. (2005, October). Stagnation, depression, constraint, and stasis: Terminological clarification. https://www.chinesemedicinedoc.com/for-practitioners/chinese-medicine-articles/

Deng, T. (2004). Practical diagnosis in traditional chinese medicine. (M. Ergil & Y. Sumei, Trans.) Churchill Livingstone.

Jingyi, Z. & Xuemei, L. (1993). Patterns & practice in chinese medicine. Eastland Press, Inc.

Maciocia, G. (2015). The foundation of chinese medicine: A comprehensive text (3rd edition). Elsevier.

Scheid, V., Bensky, D., Ellis, A., & Barolet, R. (2015). Chinese herbal medicine: Formulas & strategies (2nd edition). Eastland Press, Inc.

Wiseman, N. & Feng, Y. (2014). A practical dictionary of chinese medicine (3rd edition). Paradigm Publications.